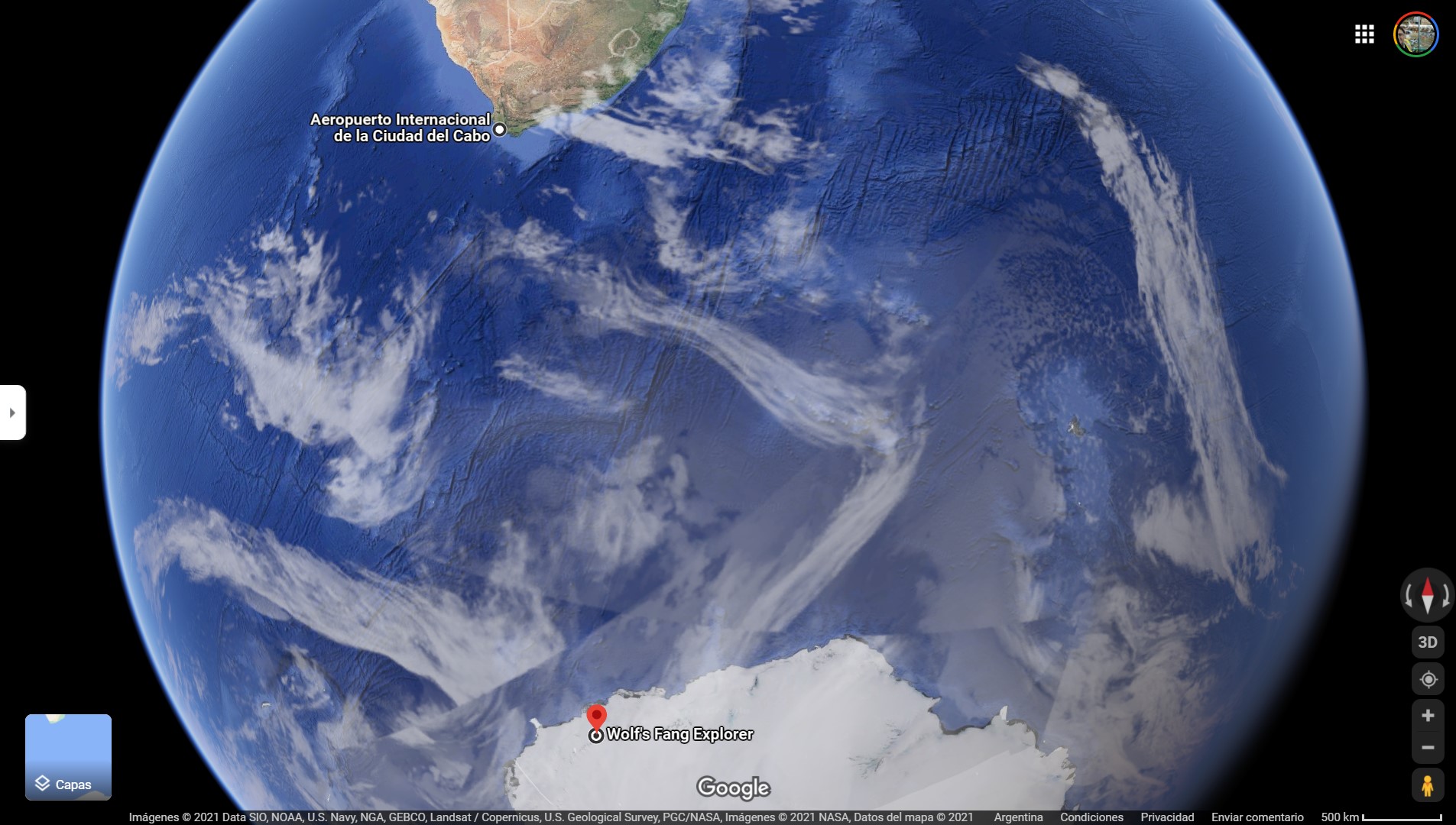

00After covering 2,500 nautical miles (4,300 kilometers) in just over five hours from Cape Town, Hi Fly’s A340-313HGW, registration 9H-SOL, made history this November by becoming the first aircraft of this family of Airbus four-engine aircraft to operate a flight in Antarctica.

According to the company, this aircraft will be used during this season to transport a small number of tourists, scientists, and essential cargo to the white continent.

Hi Fly also shared Captain Carlos Mirpuri’s diary (also Vice President of the airline), who was in charge of this historic mission.

It is reproduced below.

Hi Fly 801/802 – November 2, 2021

The crew met and departed from the Cape Town hotel at 5 a.m. local time. Transportation took 30 minutes to the airport. The formalities took another 30 minutes and we arrived at the plane at 6 a.m., two hours to our scheduled departure time.

The engineers and ground operations staff had left the hotel an hour earlier, so by the time we arrived at the aircraft, refueling had been completed and the cargo was being loaded. We were expecting 23 passengers, all of the client personnel, and since this was the first flight of the season, most of the ground support equipment we would need at WFR (Wolf’s Fang Runway, Antarctica) was in our cargo compartments. These first two sorties are solely to establish the Antarctic operation, looking ahead to the 2021/2022 summer season.

The 2,500 nautical miles between CPT and WFR would take us 5h 10m outbound and 5h 20m return. As this was the first flight, with limited ground support, we planned a 3-hour turnaround at WFR.

It was going to be a long day for the crew, but the emotion of participating in such a unique event was above all else.

As usual, we started with a briefing for the crew upon arrival at the aircraft. This is not just another flight, there are specifics related to this very remote operation we were about to undertake, the harsh environment we would be dealing with and the need to make sure there was adequate protective clothing on board.

While the cabin checks and catering loading were taking place, my crew and I were inspecting the aircraft, checking its systems, loading the route into the navigation computers, and reporting the details of our departure.

The passengers arrived 20 minutes before the estimated departure time. It was exactly 8 a.m. local time when we left the gate. Punctuality. Always. This is Hi Fly’s motto.

We lined up on runway 01 but had to stop for a moment before takeoff; I detected heavy bird activity on the runway and asked the tower to roll the truck in charge of chasing them away, they eventually moved out of the way. The last thing we want is for a bird to hit and damage the engine on any flight. At 8:19 a.m. we were finally in the air. A beautiful morning in Cape Town and magnificent views.

There is no fuel at WFR. We are carrying 77 tons of fuel. The 9H-SOL is an A340-313HGW (High Gross Weight) with a maximum takeoff weight of 275 tons.

It is an aircraft that delivers, every time. Robust, comfortable, and safe, it performs well in this environment.

Its 4-engine redundancy and long range make it the ideal aircraft for this type of mission.

The route to WFR was pretty much straightforward, after complying with the instrument departure procedure clearance issued by CPT air traffic control. We were soon delivered to oceanic Johannesburg via CPDLC / ADS, thus avoiding the exhausting and noisy long-range HF communication dating back to the 1950s. Digital communication is the norm today in most air navigation regions. We only lost the data-link connection 250 miles before the WFR. But about 180 miles from the destination we were able to reach Wolf’s Fang on VHF. No air traffic control, just a person with a portable handheld radio watching the runway. And, they indeed take very good care of its condition.

South of 65 degrees we return to polar navigation techniques and use the true track as a reference.

A chart is also used to ensure that we do not deviate from the course. During the trip, we receive via ACARS (another digital communication system), frequent weather reports from WFR that are passed to us via our operations in Lisbon. The WFR guys have an Iridium satellite phone, the only means of communication from that part of the world. The meteorologists do a great job, and we only launch in Antarctica when the weather meets our requirements. But a forecast is a forecast, and when flying to the end of the world you need to frequently make sure that the actual weather matches up with the forecast.

The weather looked great, and as we were approaching the top of our descent we were also supposed to get runway friction reports passed to us. This is measured by a properly equipped car, which runs the length of the track taking measurements every 500 meters. The frictions were also all above what we consider to be the minimum, so we started our descent.

Carrying fuel to cover both legs means we would be landing with a maximum weight of 190 tons. Add in the fact that we were operating on an airfield carved out of blue glacial ice, and it’s easy to understand why the first landing of an Airbus A340 there would attract a lot of attention and anxiety. But at the head office, we were confident that we had done our best to do our homework.

Several months of preparation for this flight were carried out by our operations department and the success of our first landing is testimony to a job well done.

We even had a visit to WFR, in a business jet carrying scientists, two days before our flight, by Captain Antonios Efthymiou. It is considered a category C airport, and except for this first flight, all the crew had observed a flight from the cockpit before operating.

The glacial blue ice rink is hard. It can support a heavy aircraft on it. Its depth is 1.4 km of ice-free of hard air. Most importantly, the colder it is, the better. The grooves are carved along the runway with special equipment, and after cleaning and carving a proper braking coefficient is obtained; the runway being 3000 meters long, landing and stopping such a heavy A340 on that airfield would not be a problem. At least not on paper, since no A340 has ever landed on the blue glacier ice before.

The glare is terrible, and proper goggles help you adjust your eyes between the outside view and the instrumentation. The non-flying pilot has an important role to play in making the usual warnings, plus additional ones, especially in the latter stages of the approach.

It is not easy to spot the runway, but at one point we have to see it, as in WFR there is absolutely no navigational aid and from about 20 miles out we must be in visual contact.

We finally spot the runway alignment and start setting up in advance, selecting flaps and landing gears to be fully stabilized 10 miles before the runway. There is also no visual guidance of the glideslope, and the blending of the runway with the surrounding land and the vast white desert that surrounds it makes altitude judgment challenging to say the least.

Altimeters in cold weather also suffer from temperature errors and need adjustment. All this was taken into account. We made a textbook approach for an eventful landing, and the aircraft performed exactly as planned. When we reached taxi speed, I could hear a round of applause from the cockpit. We were happy. We were, after all, writing history.

The turnaround time was much less than the 3 hours expected. Our flight and ground operations did an impeccable job, as did our engineers. A truly winning team. Equipped for the extreme cold we ventured outside, greeted people, saw details and runway locations for added confidence in the system put in place. All looks good for launching repeatable operations to and from Antarctica.

Takeoff was smooth, as was the return flight. The customer was happy, we were happy. All the objectives of this first flight had been met. The event was recorded by our reporter Marc Bow.